Reflecting on a lifetime of service

The below article was written for Purdue University’s School of Languages and Cultures’ summer 2023 graduate student newsletter.

I want to express my gratitude to the staff of the Purdue University Archives and Special Collections for their generosity in helping me navigate their resources. I am also deeply appreciative of Dr. Mary O’Hara, whose dissertation on the life and work of Williams (Let it Fly: The Legacy of Helen Bass Williams) richly contributed to the materials on file in Purdue’s library.

I would also like to thank the Helen Bass Williams Academic Success Center for their helpful timeline on Williams’ life that distills many key milestones in her work and activism.

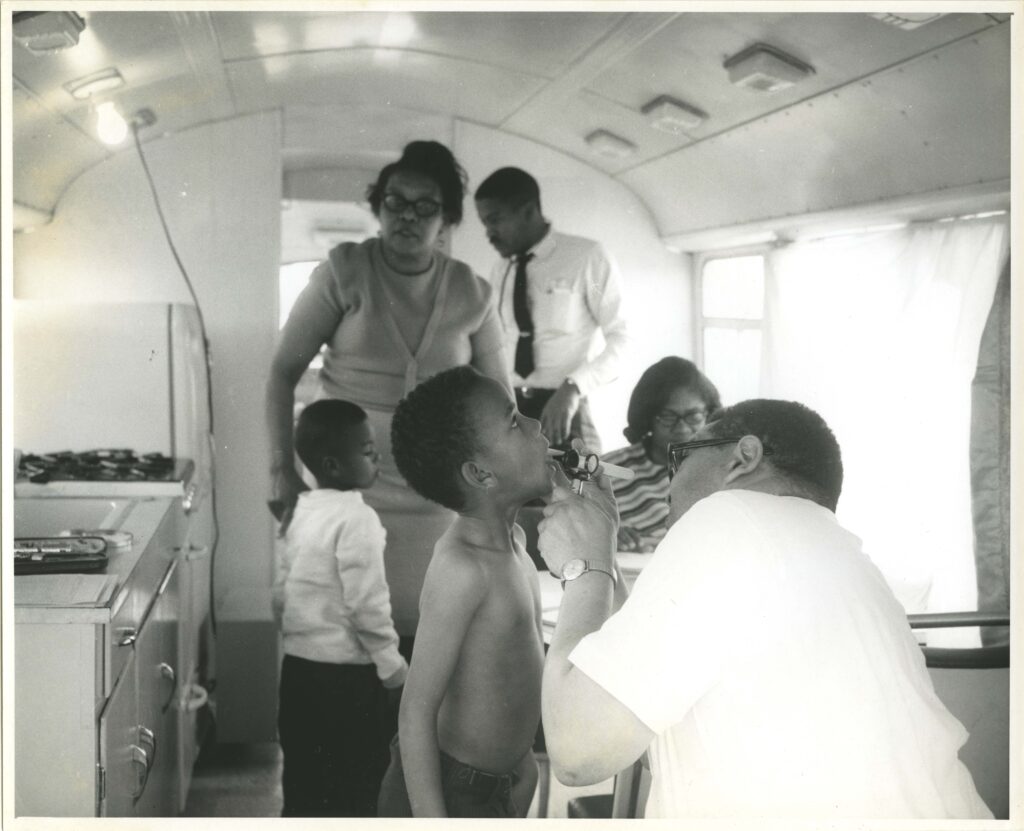

Image courtesy of Purdue University Archives and Special Collections

Growing up

When we enter into conversation about someone like Helen Bass Williams, it’s easy to walk out the highlights reel. The awards won, the distinctions—the legacy. The danger is in missing the finer details; the humanity exuded through formative moments.

The Mary O’Hara Archives captures such a moment in Williams’ childhood, growing up in an apostolic church—something she enjoyed. That is, until all the children in the church were invited to the prayer bench one day to receive the Holy Spirit. Williams describes how everyone else had gone up except for her.

“I was the only sore thumb,” she says. “All the kids were gettin’ mad with me.”

Despite the appeals (“C’mon, Helen!”), she refused to budge. This went on for days. By the fifth night, her mom was furious.

“You think you’re too good?” she asked. But for her daughter, it was a matter of principle. She was supposed to feel the Holy Ghost—and she couldn’t.

“I thought making them go up on the [prayer] bench and prayin’ over ‘em and shoutin’ over ‘em was a lot of bullshit.”

And that’s when it happened. She felt the Holy Ghost. She describes it as a “calm sweetness” that swept over her.

“I will always believe it was the Holy Ghost,” Williams says. Still, she refused to go up to the prayer bench.

“I was too mean to let my mother know I had felt it and never went up.”

In the years to come, Williams would need that meanness and stubbornness.

Before Purdue

Williams spent the 1950s and 60s involved with the civil rights movement in the southern United States.

For Williams, activism was a way of life motivated by love of community. A 1986 article describes how Williams eschewed more visible roles within the movement for the “outback of the Mississippi delta,” where she “registered blacks to vote and sat in local post offices to help them fill out social security forms or read the fine print.”

Against the backdrop of the institutional terrorism of the Jim Crow regime, Williams’ committed herself to building political power—but she was equally attentive to the daily aspects of people’s lives. A letter written by William P. Davies, president of the Mississippi Baptist Seminary, describes how she would pack up her car on Sundays and look for a church where she could “show them how to prepare commodity foods” and “talk with them about better ways of feeding their families.”

Davies details Williams’ generosity, which included providing a warm welcome to strangers needing a place to stay en route to other points. “She did not lock her door,” Davies writes, “and felt it was a deep privilege to have people feel that they could use her house.”

Reflecting on this period of her life, Williams wrote, “Life in Mississippi was a privilege within itself. To be alive and able to serve in any meaningful capacity was a special blessing” (emphasis Williams’).

During her time in Mississippi, she worked alongside Ed King, Amsey Moore, and famed movement leader Fannie Lou Hamer. She also crossed paths with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., at the march in Selma where her “spirited resourcefulness” came in handy. The July-August 1986 issue of the Prairie Citizen describes the encounter.

“As Helen and other black leaders knelt in a prayer circle, police dogs snapped and growled an inch behind their heads. ‘Martin (Dr. King) sweated and prayed and sweated—he was afraid of the dogs.’ But Helen had decided to win the dogs over, so she brought rancid hamburger to coat her fingers. The dogs stopped straining at their leashes to sniff, and to the annoyance of their handlers, to lick her fingers.”

The work continues at Purdue

According to the May-June 1975 issue of the Perspective, Williams “came to Purdue in part because she felt that her civil rights activities had so provoked the racists that her life might be in danger if she stayed in the South” (10). But her work couldn’t be stopped. As the first African American faculty member on Purdue’s campus, Williams had a critical role to play in West Lafayette.

In a letter to friends and supporters in Greater Lafayette, Williams details her work outside the classroom. The four-page letter opens by giving us a picture of this group of friends to whom Williams addresses the letter. “You are the only local committee of which I am aware that functions to assist in a Purdue University program and all of you should have awards,” Williams writes (emphasis Williams’). “In one way or another, things have been easier for blacks here because of you.”

The letter outlines the way that Williams and this committee helped to support students on Purdue’s campus. “What happened with your money?” Williams asks. “Well, teeth were fixed and one very pregnant young woman drove over to 57 South, wound up in Mississippi where she had her baby, drove back and all for less than $300. She needed over $800 here and her husband simply didn’t have it. SO, YOU BROUGHT LIFE.” (Emphasis Williams’.)

There was one bit of the letter that I had to reread, where Williams rather casually mentions an incident involving her dog. “Mama Dog (my 19 year old sooner) had a nervous break-down when one of the 13 students sleeping on my floor took off her tennis shoes.” (Emphasis my own.)

In the same letter, Williams acknowledges her own limitations as she aged. “Many [students’] parents living in Gary,” she writes of the African-American majority Chicago suburb, “have called me asking if they can come work for me and live with me until they find jobs!” Besides jobs being scarce in Lafayette, the moment had passed for Williams. “Relocation I did plenty of in Mississippi,” she writes. “It, like children, is for the young and at 60, I cannot begin it here.”

Already, she was dreaming of returning home to the “yellow clay country of Southern Illinois where all 250 of the inhabitants are living on Social Security and are over 60 or under 12.”

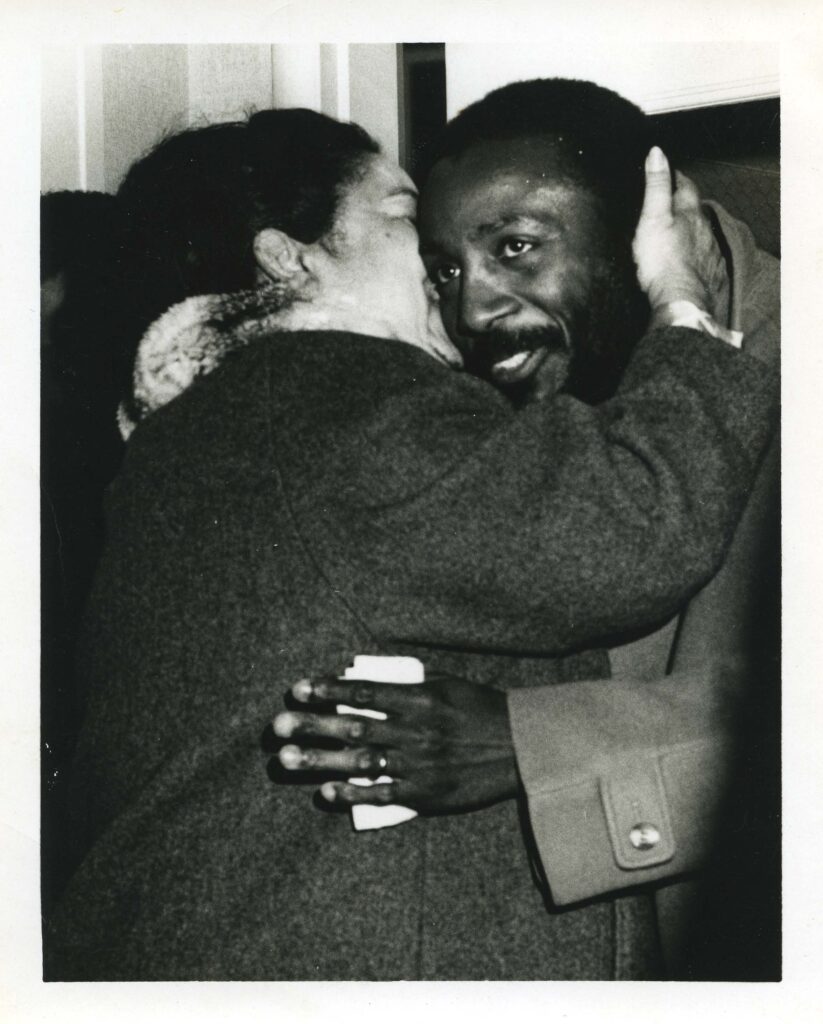

Image courtesy of Purdue University Archives and Special Collections

In reflection

Reflecting on Williams’ passing in 1991, Journal & Courier columnist and university historian John Norberg wrote, “There is no building at Purdue named for Helen Bass Williams. There’s just a spirit—a spirit that needs to be carried on in her name.”

It would be easy to stop there. To close with Norberg’s words and move on. But I can’t do that.

I can’t do that because, although there are parts of Williams’ story that are utterly foreign to me (like the idea of students’ parents calling and asking for a place to stay while they look for work), others feel all too familiar.

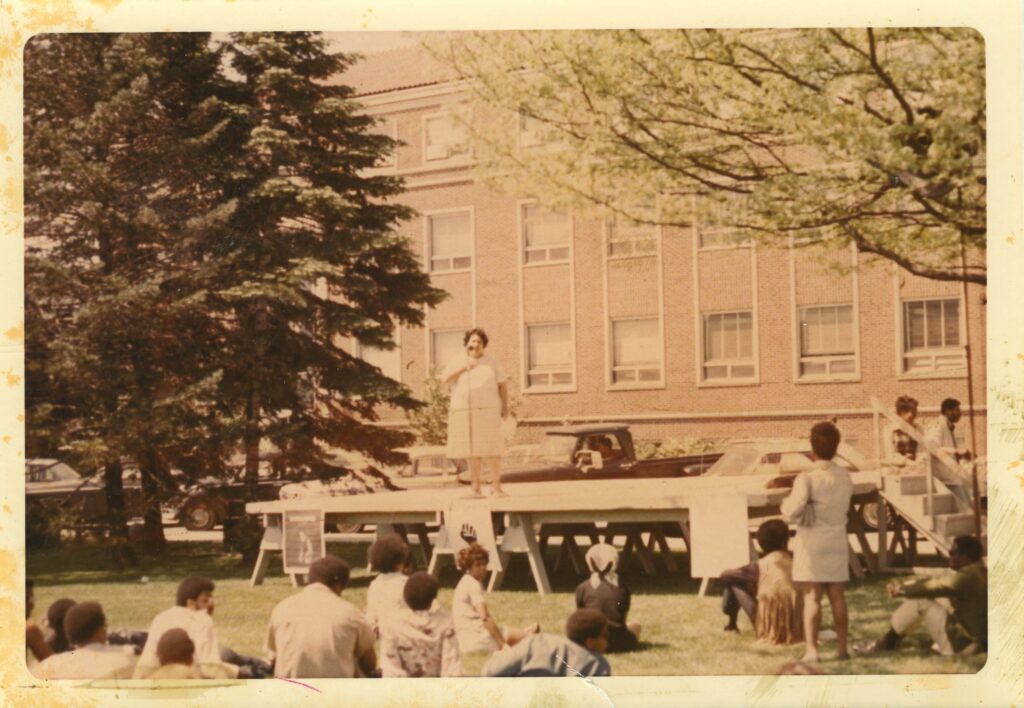

For example, take the trove of photographs depicting life in Mississippi in the 1960s. For me, the images of a mobile children’s health clinic evoked more recent events in Flint, Michigan, in the wake of the water crisis that left thousands of disproportionately impoverished Black children facing the lifelong (and generational) effects of lead poisoning. Some of the images capture the carefree joy of the young; others are haunting, documenting the physical ailments of those same five- and six-year-olds.

The work to which Williams dedicated her life remains unfinished. It remains for each of us to examine what it is we can do to help further it.